Lessons from an 8’x8’ Photography Studio

6 months ago, I googled “How big should a photography studio be?”.

I had just moved into the largest bedroom of my 5 person Seattle house, and was looking at all the new space I had. After positioning my bed and furniture on one half of the room and using a clothing rack as a room divider, I was left with an empty space slightly more than 8 feet long in both directions. It was at this moment that I Googled the above question—

A photography studio that is 1,250 square feet (16.13 sq m) or more is preferable in most cases. However, 625 square feet (58.06 sq m) will do the job and might be best if the studio typically does smaller photoshoots.

I was nowhere near the 625 square feet required for “smaller photoshoots”, and this was going to be a problem for a wide variety of reasons I only now understand. If I use a wider lens, the backdrop won’t be wide enough to cover the whole shot. If I use a tighter lens, I won’t be able to get far enough from the subject for the lens to focus, or even capture more than just a close-up on their face. If I use a white background, I’ll need to light it separately, and that light will spill all over the subject if they’re not far enough away. Even without a background light, I should leave 4-8 feet between my subject and the background to avoid casting a shadow. I also need higher ceilings to have enough room for backdrop suports, lights, and headroom above a standing person.

“Whatever, I’ll figure it out”, I thought.

Alex sits for a portrait.

After taking some photos of friends and realizing how easy it was to take professional-looking picture, I put out a call on social media offering $10 headshots. Alex was one of the first people to reach out, saying she was in need of a LinkedIn makeover and would love to stop by.

As she sat for her headshot, we tried a few different backgrounds and poses and I nervously mumbled things while changing around lights. About 15 minutes in, I said “We got it! We got all the photos we need”.

I struggled with space constraints during our shoot, but I began to feel a different problem arise. I have always felt panic when taking photos of people, and I have an extremely strong urge at every moment to say “We’re good! That’s a wrap. You can go home now, I got all the photos I need”. And it would be a lie. I want to end the shoot because it’s really hard to take pictures of people.

Self portrait.

I struggle with anxiety. I get really nervous in ambiguous situations, and I want it all to stop. In addition to this, it is extremely difficult to take photos of people, because people generally don’t like having their photo taken. Look at a photo of someone smiling and saying “cheese”, and you will not see raw humanity looking back at you. You will see someone putting on a facade, showing only what they want you to see.

Portraits are a specifically challenging medium for me for these reasons. By default, any photo session will begin with the subject closed-off and nervous while I am have racing thoughts and may a manic demeanor.

In therapy, I have been exploring a path from anxiety into vulnerability and rawness. I could tell someone I was taking photos of “I get really anxious when taking portraits”. The vulnerability of sharing that I feel this way can be a path towards trust and mutual understanding of the other, and could be the first step towards a real, human relationship. If I can tell them that I want to push though my anxiety because the pursuit is extremely meaningful to me, maybe I can lead them in a similar direction.

Instead of running from my discomfort, I can embrace it and use it as my path towards meaning. And I can use this framework to learn all kinds of lessons that will have benefits far beyond portrait photography.

Mary sits for a test portrait while I setup lights.

One strategy that proved effective of pushing past this anxiety barrier is taking photographs of people who already trust me. I scheduled headshots with two Seattle dancers, but beforehand, I had my partner sit down while I set up some lights. Having her in front of the camera meant I wasn’t scared anymore, because the person looking back at me was comfortable with me. There’s a magic to close relationships, and it can be a way to explore more uncomfortable aspects about yourself with the safety of someone who will be there for you.

Mary holds a reflector while Erika sits for a portrait.

Another strategy that proved effective was to have a “creative assistant” help with shoots. This role is actually just someone to make the subject feel comfortable. In the photo above, Mary is technically assisting by holding a reflector, but truthfully she’s providing her presence. If the mood is off or if I get distracted with a frustrating lighting issue, Mary is there with her humanity to keep a casual conversation going and laugh at everyone’s jokes. It’s amazing how much she has improved both the mood in the room and the final images in every shoot she’s been apart of. By appreciating Mary’s unique talents, I turned a solo project into a creative collaboration to showcase more than just my abilities.

Henri sits for a portrait.

A strategy Sean Tucker suggests in “Photographing People: The War in Every Portrait” to swap places with your subject. By giving them the camera and sitting in front of it, you reverse the power dynamic and one-sided nature of portrait photography. During a shoot with Henri, we continuously switched places and were able to talk out-loud about how the light was working and instantly see examples on each other’s faces. We were no longer a “photographer” and “photographed”, but instead we were working together towards a common goal. The photos I took of Henri are some of my favorite to have been taken in my studio, and his eyes feel human and raw in a way I desperately want to capture in others.

Bri sits for a portrait.

One of my favorite lessons I’ve learned is to simply take time to talk. I hadn’t seen Bri in a few years, and when we reconnected for headshots in the studio, it was over an hour before I even turned my camera on. We caught up and told each other stories, and as I sat with her I was fully present. It was the experience I had been pursuing for months, and counterintuitively, it only happened because I completely set aside photography. By not trying to solve every problem at once, I could be fully present with the person in front of me.

Charlie and Aliyah sit for a couples portrait.

I have also learned that in photos and in life, it is often more fun to slow down. By not rushing through a shoot, I can take time to enjoy subtle moments and help manage any underlying anxiety I might be experiencing. Charlie and Aliyah reached out for a couples shoot and I excitedly had them over. We sat, chatted and leisurely had some beers while we talked about what we wanted to get from the session. Afterwards, we took the time to look through all of the photos so they could pick their favorites. I felt my usual rushed feeling of “let’s get this over with”, but I forced myself to take all the time we needed and relax a little. We tried different poses which looked okay, but it was the candid moments between poses when they showed their true selves. Had I rushed through the shoot, I would have missed every meaningful moment that made this experience so special.

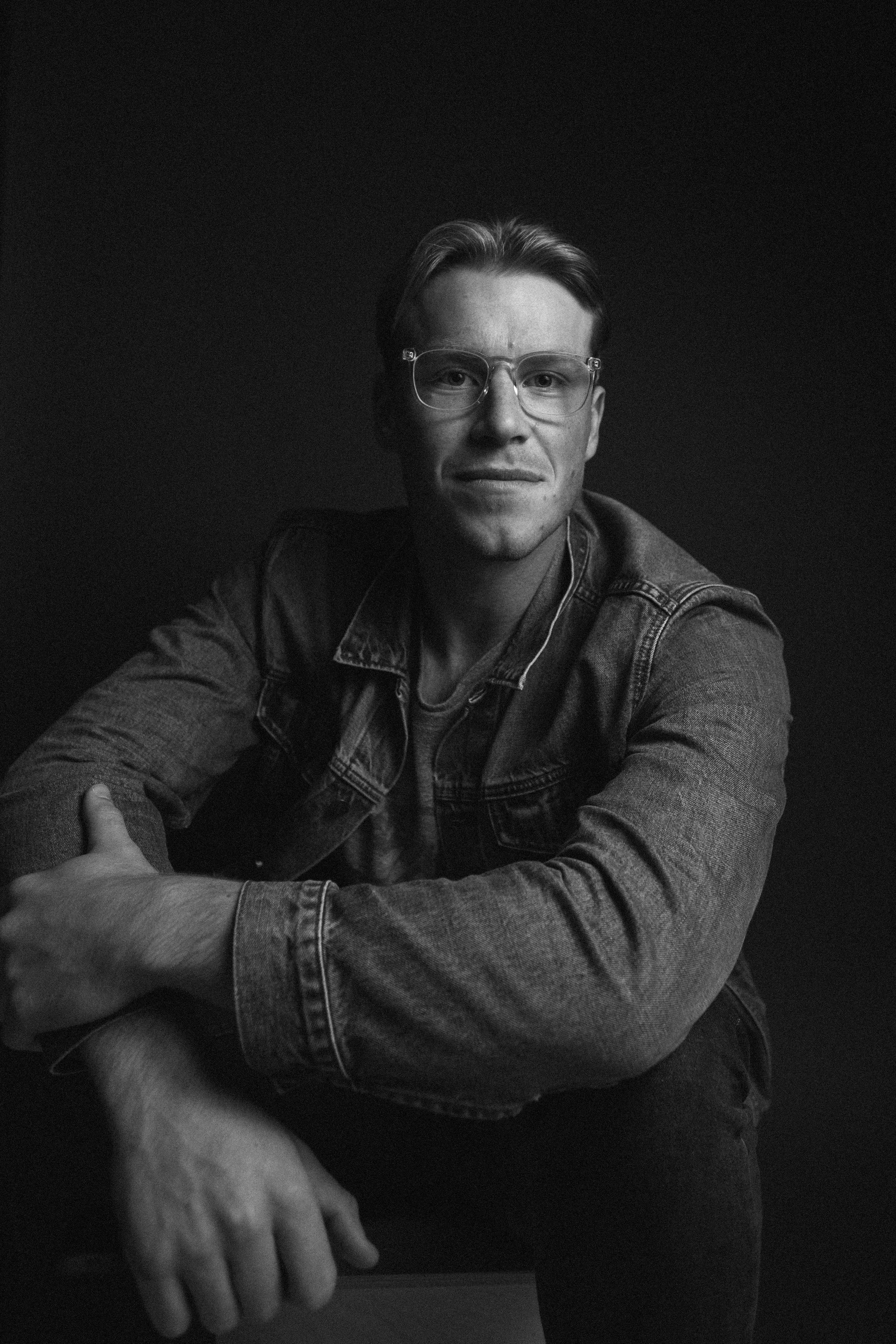

Michael sits for a portrait.

The most important lesson I’ve learned is that portraits are a worthy struggle. I usually like to capture existing moments without getting involved, so in portraits I have picked one of the hardest forms of photography for myself. On top of that, I learned to do it in a space so small that almost one one believes it’s actually my studio when they see it in person.

I hope to continue learning lessons in this limited space. This practice will make me a better photographer outside of this small, controlled environment. And I have no doubt will have lifelong impacts to make me a better, more vulnerable and present person.